Mrs Whatsit attempts to explain a tesseract, and L’Engle commits a heresy!

“[He {Meg’s father} is behind the darkness, so that even we cannot see him].”

I think I’ll simplify Mrs Which’s dialogue like this from here on out, because it’s easier for me to write (and for you to read) than duplicating the drawn-out words. It’s a neat concept for a character that is only loosely attached to the material world, but it’s hard for some people to read.

Meg began to cry, to sob aloud. Through her tears she could see Charles Wallace standing there, very small, very white. Calvin put his arms around her, but she shuddered and broke away, sobbing wildly. Then she was enfolded in the great wings of Mrs Whatsit and she felt comfort and strength pouring through her. Mrs Whatsit was not speaking aloud, and yet through the wings Meg understood words.

“My child, do not despair. Do you think we would have brought you here if there were no hope? We are asking you to do a difficult thing, but we are confident that you can do it. Your father needs help, he needs courage, and for his children he may be able to do what he cannot do for himself.”

Yeah, Calvin may be sympathetic, but as Mrs Whatsit said earlier, it’s not his father whose life is at stake.

“[We must go behind the shadow.]”

“But we will not do it all at once,” Mrs Whatsit comforted them. “We will do it in short stages.” She looked at Meg. “No we will tesser, we will wrinkle again. Do you understand?”

“No,” Meg said flatly.

Yeah, Mrs Whatsit hasn’t actually explained tessering yet. But no time like the present!

Mrs Whatsit sighed. “Explanations are not easy when they are about things for which your civilization still has no words. Calvin talked about traveling at the speed of light. You understand that, little Meg?”

“Yes,” Meg nodded.

“That, of course, is the impractical, the long way around. We have learned to take shortcuts wherever possible.”

“Sort of like in math?” Meg asked.

“Like in math.” Mrs Whatsit looked over at Mrs Who. “Take your skirt and show them.”

[…]

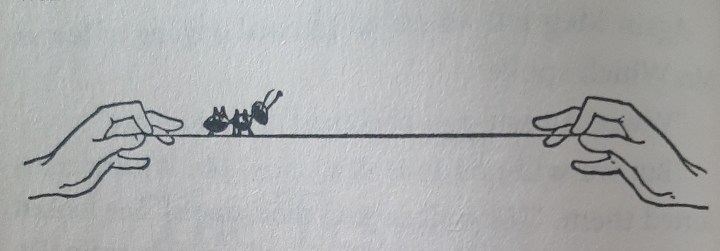

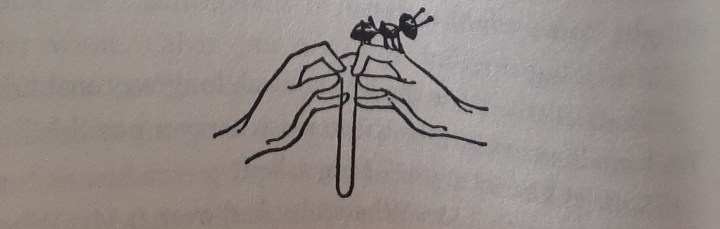

“You see,” Mrs Whatsit said, “if a very small insect were to move from the section of the skirt in Mrs Who’s right hand to that in the left, it would be quite a long walk for him if he had to walk straight across.”

Swiftly Mrs Who brought her hands, still holding the skirt, together.

“Now, you see,” Mrs Whatsit said, “he would be there, without that long trip. That is how we travel.”

This seems to be a good enough explanation for Charles and Calvin, but Meg still doesn’t get it. As Charles actually wheedled an explanation about the tesseract out of his mother, though, Mrs Whatsit outsources the exposition to him.

“Okay,” Charles said. “What is the first dimension?”

“Well – a line.”

“Okay. And the second dimension?”

“Well, you’d square the line. A flat square would be the second dimension.”

“And the third?”

“Well, you’d square the second dimension. Then the square wouldn’t be flat anymore. It would have a bottom, sides, and a top.”

“And the fourth?”

“Well, I guess if you want to put it into mathematical terms you’d square the square. But you can’t take a pencil and draw it the way you can with the first three. I know it’s got something to do with Einstein and time. I guess maybe you could call the fourth dimension Time.”

“That’s right,” Charles said. “Good girl. Okay, then, for the fifth dimension you’d square the fourth, wouldn’t you?”

“I guess so.”

“Well, the fifth dimension’s a tesseract. You add that to the other four dimensions and you can travel through space without having to go the long way around. In other words, to put it in Euclid, or old-fashioned plane geometry, a straight line is not the shortest distance between two points.”

Meg finally gets the concept (at least enough to proceed with), so they prepare to tesser again.

Unfortunately, Mrs Which stops on a “two-dimensional planet” (which shouldn’t be physically possible), and it’s painful for all the humans, but it’s evidently fun for the Mrs W’s (and Whatsit and Who get a kick out of Mrs Which making a mistake). But this slip-up reminds Meg of how much her mother would be worrying.

“Just relax and don’t worry over things that needn’t trouble you,” Mrs Whatsit said. “We made a nice, tidy little time tesser, and unless something goes terribly wrong we’ll have you back about five minutes before you left, so there’ll be time to spare and nobody’ll ever need to know you were gone at all, though of course you’ll be telling your mother, dear lamb that she is. And if something goes terribly wrong it won’t matter whether we ever get back at all.”

“[Don’t frighten them],” Mrs Which’s voice came. “[Are you losing faith]?”

“Oh, no. No, I’m not.”

But Meg thought her voice sounded a little faint.

Anyhow, they’ve come to the planet where resides the Happy Medium, who spends her days looking out at the universe through a crystal ball (and generally being happy).

“Oh, Medium, dear,” Mrs Whatsit said, “these are the children. Charles Wallace Murry.” Charles Wallace bowed. “Margaret Murry.” Meg felt that if Mrs Whatsit and Mrs Who had curtsied, she ought to, also; so she did, rather awkwardly. “And Calvin O’Keefe.” Calvin bobbed his head. “We want them to see their home planet,” Mrs Whatsit said.

The Medium lost the delighted smile she had worn till then. “Oh, why must you make me look at unpleasant things when there are so many delightful ones to see?”

Again Mrs Which’s voice reverberated through the cave. “[There will no longer be so many pleasant things to look at if responsible people do not do something about the unpleasant ones].”

They came here to make the full gravity of the situation clear.

Meg dropped her arm. They seemed to be moving in toward a planet. She thought she could make out polar ice caps. Everything seemed sparkling clear.

“No, no, Medium dear, that’s Mars,” Mrs Whatsit reproved gently.

“Do I have to?” the Medium asked.

“[Now]!” Mrs Which commanded.

The bright planet moved out of their vision. For a moment there was the darkness of space; then another planet. The outlines of this planet were not clean and clear. It seemed to be covered with a smoky haze. Through the haze Meg thought she could make out the familiar outlines of continents like pictures in her Social Studies books.

“Is it because of our atmosphere that we can’t see properly?” she asked anxiously.

“[No, Meg, you know that is not the atmosphere],” Mrs Which said. “[You must be brave].”

“It’s the Thing!” Charles Wallace cried. “It’s the Dark Thing we saw from the mountain peak on Uriel when we were riding on Mrs Whatsit’s back!”

When Meg asks if it just arrived on Earth while they were gone, Mrs Whatsit informs her that it’s been there since the beginning (at least of mankind), and that’s why their world is so troubled.

“I hate it!” Charles Wallace cried passionately. “I hate the Dark Thing!”

Mrs Whatsit nodded. “Yes, Charles dear. We all do. That’s another reason we wanted to prepare you on Uriel, We thought it would be too frightening to see it first of all about your own beloved world.”

“But what is it?” Calvin demanded. “We know that it’s evil, but what is it?”

“[You have said it]!” Mrs Which’s voice rang out. “[It is Evil. It is the Powers of Darkness]!”

“But what’s going to happen?” Meg’s voice trembled. “Oh, please, Mrs Which, tell us what’s going to happen!”

“[We will continue to fight]!”

[…]

“And we’re not alone, you know, children,” came Mrs Whatsit, the comforter. “All through the universe it’s being fought, all through the cosmos, and my, but it’s a grand and exciting battle. I know it’s hard for you to understand about size, how there’s very little difference in size between the tiniest microbe and the greatest galaxy. You think about that, and maybe it won’t seem so strange to you that some of our very best fighters have come right from your own planet, and it’s a little planet, dears, out on the edge of a little galaxy. You can be proud that it’s done so well.”

“Who have our fighters been?” Calvin asked.

“Oh, you must know them, dear,” Mrs Whatsit said.

Mrs Who’s spectacles shone out at them triumphantly, “And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.”

“Jesus!” Charles Wallace said. “Why of course, Jesus!”

“Of course!” Mrs Whatsit said. “Go on, Charles, love. There were others. All your great artists. They’ve been lights for us to see by.”

“Leonardo da Vinci?” Calvin suggested tentatively. “And Michealangelo?”

“And Shakespeare,” Charles Wallace called out, “and Bach! And Pasteur and Madame Curie and Einstein!”

Now Calvin’s voice rang with confidence. “And Schweitzer and Ghandi and Buddha and Beethoven and Rembrandt and St. Francis!”

Notably, L’Engle gives preference to artists and scientists rather than Christian theologians like Martin Luther or (more obviously in this context) John Calvin. The only one on this list that could be categorized as a theologian is St. Francis, but similar to Jesus or Buddha, he’s known for his lifestyle just as much as for his teachings. Essentially, she only includes people who practiced what they preached.

She briefly discusses the “heresy” of this novel (that is, putting Jesus on the same level as Buddha and Einstein) in Walking on Water, explaining that she was rebelling against the German theologians she’d grown tired of, that she believed in a God who was bigger than the limits they tried to put on him. And within the context of the story, it makes sense! If there were a wider universe and many other worlds, a person who died to save this one wouldn’t seem so important.

Back to the story, Meg offers a halfhearted suggestion of Copernicus and Euclid, but is more concerned about what all this has to do with her father.

“[We are going to your father],” Mrs Which said.

“But where is he?” Meg went over to Mrs Which and stamped as though she were no older than Charles Wallace.

Mrs Whatsit answered in a voice that was now low but quite firm. “On a planet that has given in. So you must prepare to be very strong.”

Until next time…